Benin

Capital city — Porto-Novo

Country population

Incarceration rate (per 100,000 inhabit…

i2016/ Ministry of Justice and LegislationType of government

Human Development Index

i2016/ UNDPName of authority in charge of the pris…

Total number of prisoners

i31/07/2016/ Ministry of Justice and LegislationPrison density

Total number of prison facilities

An NPM has been established

Female prisoners

i31/07/2016/ Ministry of Justice and LegislationIncarcerated minors

i2016/ Ministry of Justice and LegislationPercentage of untried prisoners

i31/07/2016/ Ministry of Justice and LegislationDeath penalty is abolished

Yessince 2012

Physical integrity

Benin is a de facto abolitionist country. The last execution took place in 1987. No death sentences have been pronounced since 2010.

In 2012, the Benin government ratified the second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights aimed at abolishing the death penalty. Following this ratification, the Constitutional Court declared that “there will no longer be any legal provision referring to the death penalty”. Following the statement, the penalty of most people sentenced to death, was commuted to life imprisonment. Fourteen people are still waiting on death row. They are incarcerated away from other prisoners in the Akpro-Missérété Prison.

Human rights organizations have recommended that Parliament adopt legislative measures as soon as possible to officially remove the death penalty from its national legislation.

The life sentence is prescribed by the Criminal Code, which is currently being revised and referred to in the Code of Criminal Procedure.

Persons sentenced to life imprisonment may apply for early release (conditional or presidential pardon) after a minimum of 30 years.

Deaths in detention

Little information is available on the causes of recorded deaths. Deaths due to lack of ventilation and promiscuity in the dormitories were mentioned in reports but health informaton remained unknown.

Sixteen deaths were recorded during the second quarter of 2016 :

- Four in the prisons of Abomey and Natitingou

- Two in Ouidah and Lokossa.

- The others occurred in Cotonou and Akpro-Missérété.

Number of deaths

16

Acts of torture are not incriminated by the Criminal Code of Benin.

Cases of torture in police custody take place between midnight and four o’clock in the morning. People are beaten with truncheons and threatened with guns. They come out of those beating sessions covered with serious injuries. Policemen, or gendarmes, most often target the buttocks and lower limbs because wounds can be concealed more easily. The victims do not receive any care.

In July 2014, two young girls, Amina Adjaï and Albertine N’tcha, were beaten at the Zoka Police Station in Abomey-Calavi. ACAT Benin and FIACAT brought this case to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture. They detailed the facts in a report1 published in 2015. The following is an excerpt from it:

Circumstances around the torture¶

- Date and place of arrest

Misses Aminatou ADJAÏ and Albertine N’TCHA, both children who had been placed (called “vidomégons” in the Fon language) with Mr Alain and Mrs Leïla GBAGUIDI, worked as domestics for this family. On Tuesday, July 15, 2014, they were taking care of one of the couple’s children, Béni GBAGUIDI. Claiming that the child had been abducted, Mr and Mrs GBAGUIDI filed a complaint against the two victims at the Zoca Police Station in Abomey-Calavi. The two domestics were arrested that same day and placed in police custody at the Zoca Police Station. The torture took place throughout the 10-day police custody from Tuesday 15 July to Friday 25 July 2014, the date of their transfer to the Abomey-Calavi Prison. The two victims were released from the civilian prison of Abomey Calavi on 24 November without any charges being laid against them. The child was found by the GBAGUIDI family on July 17, 2014, he was with his uncle.

- Identity of persons in charge during incarceration

On Tuesday 15 July and Wednesday 16 July 2014, when the Chief of Judicial Police (CPJ) Hervé was head of the Zoca Police Station in Abomey-Calavi, he allegedly commanded the acts of torture which were directed by Brigadier HOUNKPATIN and executed by police officers at that time.

- Did the victims have access to a lawyer, or to family members while in police custody?

The two victims did not have any access to a lawyer while in custody. On the morning of 16 July, Miss Aminatou ADJAÏ was visited by her friend, Omar ABOU who was also placed in custody on the afternoon of 16 July at the request of the GBAGUIDI family and was also beaten to acknowledge the facts. He was released on July 17 at 9pm.

- Torture method used

The two young girls were subjected to sustained interrogation over long periods of time, with verbal threats and beatings with batons and metal wire on their bodies, particularly on their buttocks.

- photos of the victims (taken by ACAT Benin during the visit to the Abomey-Calavi Prison on 1 August 2014)

- Were there any injuries ?

Both victims were wounded on both buttocks as shown by the attached photos taken by ACAT Benin during the visit to the Abomey-Calavi Civil Prison on 1 August 2014, 15 days after the torture had been committed.

- The Objective of the Torture

The two victims were beaten to extract confessions; they told ACAT that they were forced to acknowledge the facts. The investigators would have justified these acts to obtain the “declaration of the truth”. The eldest son of the GBAGUIDI family, Bryan, was seen at the police station on 16 July; he urged the police to beat the two victims to make them confess the kidnapping of his little brother.

- Were the victims examined by a doctor ? Did they receive any medical treatment?

On 29 August 2014, the administrator of the Abomey-Calavi Civil Prison alleged in writing on that he requested that the victims be given medical care at the Calavi Area Hospital - when they were referred to prison on 25 July - because they “had injuries on their buttocks which did not allow them to sit properly”.

- Does any medical report exist ?

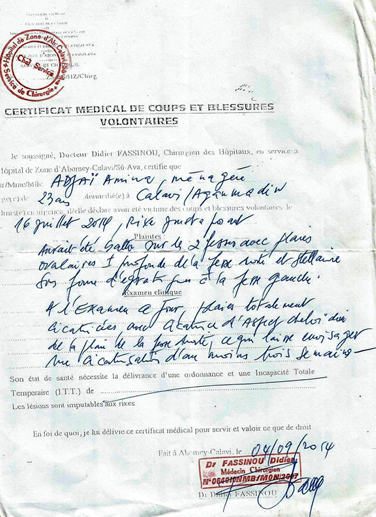

There is a medical certificate for “Bruises and voluntary wounds” concerning Miss . Aminatou ADJAÏ dated 4 September 2014. Doctor Didier Fassinou found wounds on the victim’s two buttocks. At that time the wounds were “totally healed (…) which suggests a healing of at least three weeks”.

- Medical certificate of intentional assault

- Action for reparations

A complaint of intentional assault has to be filed in the near future by the victims of the Beninese justice system, but, because torture is not a criminal offence in Benin, the deterrent effect of such action, even if completed, is fairly limited.

FIACAT and ACAT Benin stated that there are no practical provisions available for impartially examining complaints of torture, or inhuman/degrading treatment committed by officers during detentions. The latter are often covered and protected by their superiors. The Benin government does not respect its international commitments, one of which was to set up a National Preventive Mechanism (MNP) in the year following ratification of the OPCAT in 2006. Some state actors are making efforts to implement a National Observatory for the Prevention against Torture. It has yet to see the light of day.

ACAT Bénin - Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture in Benin - and FIACAT - International Federation of Christian Action for the Abolition of Torture -, Joint Alternative Report presented by the International Federation of the Action of Christians for the Abolition of Torture (FIACAT) and the Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture Benin (ACAT Benin) on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights by Benin, October 2015. ↩

International organizations, associations and litigants have reported cases of arbitrary detention. They are generally due to judicial dysfunctions. Some cases appeared to be politically motivated.

On 20 February 2015, one judge of the Porto-Novo Court ordered the immediate release of an accused who had served nine years in prison. The prosecutor authorized the release of the prisoner on 3 April, which forced him to spend another month and a half in prison. He filed a complaint with the Constitutional Court. On August 20, it ruled that the continued detention violated the provisions of the Constitution relating to arbitrary detention.